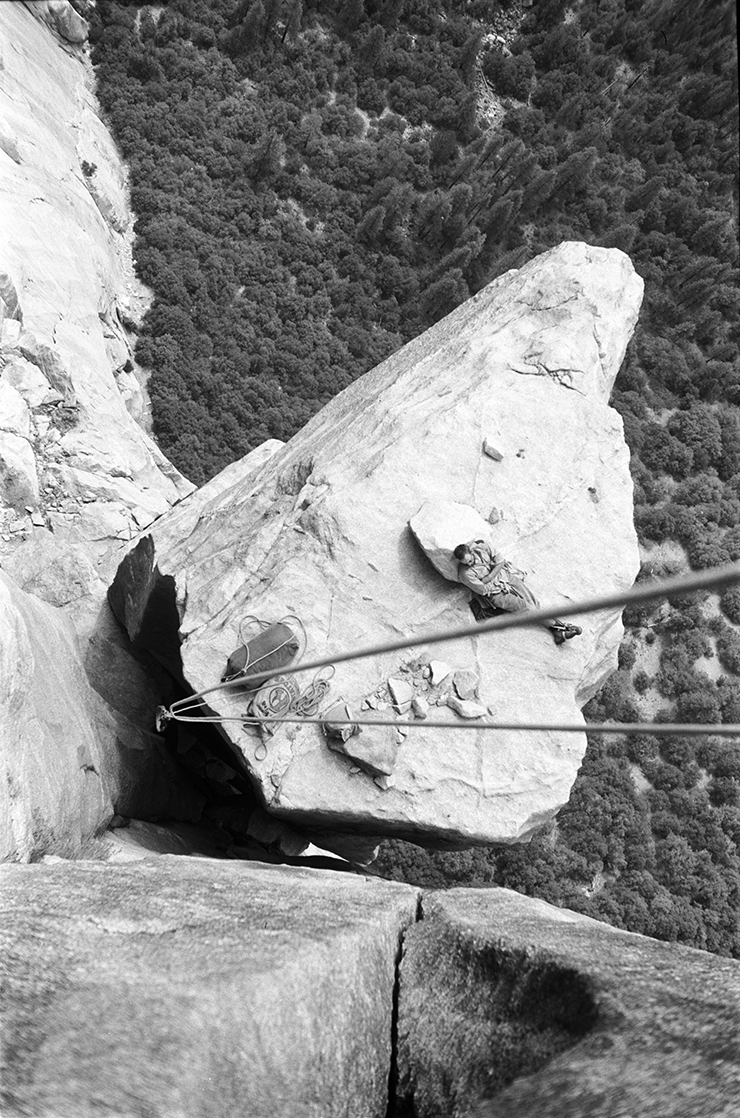

I took this picture of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson at 3:59 p.m. on January 11, 2015. At this point, I’d been living on the side of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park alongside these two climbers for 10 days, documenting their efforts to make history and complete the long-awaited first free ascent of the Dawn Wall, a 3,000-foot-tall route that was subsequently dubbed the hardest rock climb in the world.

I don’t know what it was, exactly, but the Dawn Wall story gripped the interest of people around the world in a way that I’d never seen before. Rock climbing in general is an obscure activity/lifestyle that is understood by few. But for a couple of weeks in January, climbing exploded with mainstream media attention. Incredible!

As a longtime climber and climbing photographer whose roots are deeply embedded in this small, niche world, the Dawn Wall media extravaganza was a spectacular thing to behold. Of course, I was honored and humbled to be part of a team—which included my good friends Brett Lowell of Big UP Productions, Bligh Gillies, and Kyle Berkompas, among others—that helped tell this story to the public through our pictures and video.

I was also interested to see that this photograph, with Tommy ascending the rope and Kevin preparing to climb in the portaledge, was the one that received perhaps the biggest response of all the photographs I took during those 10 days I lived on the wall and shot my climbing buddies.

What’s so interesting to me about this photograph is that it’s not a rock climbing picture, per se. From a climbing perspective, nothing particularly extraordinary is happening in this picture. In fact this could just as easily be a photo of any two weekend warriors from San Francisco.

Yet it was this picture that received the most response. It went viral on the National Geographic Instagram feed, graced the covers of newspapers, appeared on television news networks around the world, and even appeared on the cover of Rock and Ice magazine’s special “Dawn Wall” issue. Essentially, something about this photo touched both the core climbing community, and the world at large.

When I look at this picture, I can’t help but recognize that it is deeply inspired by one of my climbing and photography heroes: Tom Frost.

Tom Frost is a friend, mentor and total badass of both climbing and photography. He’s also one of the most humble guys around. As a photographer, you may know him as a co-founder of Chimera Lighting, based in Boulder, Colorado. But Tom was also a climbing pioneer during Yosemite’s Golden Age.

Tom began climbing in Yosemite with the Stanford Alpine Club, and graduated from the prestigious university in 1958. That same year, Warren Harding had just completed the first ascent of El Capitan via the Nose. In 1960, Frost became part of the team that made the second ascent of the Nose.

Frost went on to complete two more noteworthy ascents of El Capitan. In 1961, he joined up with Royal Robbins and Chuck Pratt and achieved the first ascent of the Salathé Wall, El Cap’s second route.

In 1964, this same trio as well as Yvon Chouinard completed the first ascent of the North American Wall over 9 continuous days. This was the first time El Cap had been climbed in a single continuous push (without returning to the ground); it was also considered El Capitan’s most difficult ascent to date.

Frost’s background as an inventor, engineer and businessman came together in 1972 when he and Chouinard founded Great Pacific Ironworks and started manufacturing climbing gear. This company would ultimately give birth to both Patagonia and Black Diamond Equipment, the successful apparel and climbing-gear companies that you now know today.

While all of these achievements in and of themselves constitute a most envious curriculum vitae, the reason that Tom Frost stands out to me is because his skills as a climbing photographer are, in my mind, unmatched. In fact, Tom Frost might be the most naturally talented, and unsung, adventure photographer in the world.

You’d be excused for not knowing any of this, though, because Tom is one of the most humble guys on the planet. Humility, it seems, is a characteristic that appears to be common to many people who are truly great El Cap climbers—Tommy Caldwell, I’m lookin’ at you!

For example, I only learned about Tom’s extraordinary photographic skills in a most unusual and unsuspecting way.

As a part owner of the Aurora Photos stock photography agency, over the years I have spent a lot of time reviewing pictures from the top outdoor adventure photographers in the world. I live, eat and breathe adventure photography. So it’s rare that I come across a photographer who really blows me away with his or her raw talent or entirely new way of seeing the world.

So rare, in fact, that it’s happened only once.

Several years ago, I approached Tom with the idea of becoming a contributor to Aurora Photos and archiving his photographs to make them available to future generations in a searchable online database. He was excited about the idea, so I made the five-hour drive through the Sierra foothills to Frost’s home in Oakdale, California. Tom and his wife, Joyce, welcomed me, fed me and wanted to hear all about my travels, adventures, business and love life, as I had just started dating Marina (now my wife).

After catching up, it was time to get to work. With loupe in hand, ready to edit, Tom led me to his desk, where he had the light table ready. His shelves were lined with film-filled binders. The negatives and contact sheets were meticulously organized—numbered and arranged by date. The organization clearly speaks to Tom’s mind as an engineer.

I grabbed binder number one, roll number one, and began looking at the contact sheets, occasionally checking the negative to see if the image was sharp. Some of these images were marked with a grease pencil, and they were the ones that I recognized as some of the most iconic photographs of Yosemite’s Golden Age. In between those more recognizable shots were other pictures that I found to be just as fantastic, if not better.

It felt amazing to be looking at what is arguably rock climbing’s most important moments—it’s very genesis as a modern adventure sport—while the very founder himself sat right beside me, recounting one incredible story after another behind each and every frame.

I couldn’t believe what I was looking at. Roll after roll, each negative was unique and interesting. There were no motor-driven sequences, fired in the hopes that one frame would be in focus and show a decisive moment. Tom had shot no more than a frame or two per scenario—but he had always nailed one. That one was perfectly exposed and composed, capturing a wonderful decisive moment and telling an incredible visual story about the character and spirit of Yosemite’s earliest climbers.

I was impressed with his level of technical proficiency and obvious understanding of photojournalism—of using his camera to tell a wonderful story with each shutter depression.

I had become completely engrossed in pouring over this archive, so engrossed, in fact, that I didn’t realize that hours had already passed.

“Corey, let’s take a lunch break,” Tom suggested. Reluctantly I put my loupe down, and Tom and I went to a nearby Mexican restaurant for some burritos, another passion we both share.

We talked about business and big-picture ideas, but I was really keen to grill Tom about his photographic background. Where had he learned how to use a camera? What was this extraordinary photojournalistic background that drove him to capture the original founders of our sport with such expertise, skill and creativity?

“How long had you been shooting before you began documenting Yosemite climbing?” I asked Tom. “I started on roll one today, but obviously that’s just your climbing archive. Tell me about your photography experience before that.”

Tom’s response was one of confusion. So I clarified myself and asked again. “What had you shot before this?”

With the deadpan tone that any engineer uses to deliver facts, Tom simply stated, “That binder you started with today—number one—that was the beginning. That was my first roll.”

“What!?”

I would’ve fallen out of my chair except for the fact that we were both sitting in a booth. Most people spend a lifetime trying to master the art and craft of photography, but Tom’s keen eye and raw talent were evident in his very first roll of film.

“It was 1960,” Tom explained, “And I was standing in Camp 4 with Chuck Pratt and Royal Robbins. We were racking up for what would be the second ascent of the Nose. Then Bill Furror comes over and just hands me his Leica camera. And he said to me, ‘Hey, Tom. Take this up with you. You’ll want it.’ So that’s how it started.”

To become familiar with the camera, Tom shot his first scenario, creating the now iconic image of Royal and Chuck sorting pitons on the Camp 4 picnic table, as Bill looks on.

“I was no photographer or photojournalist,” Tom clarified humbly. “I was just a climber who carried a camera.”

This was where it all began. Not only had Tom pioneered Yosemite big-wall climbing, but at the same time, he pioneered adventure photography. In the photography world, I had never seen such raw virtuosity and talent before or since.

In light of the Dawn Wall media extravaganza, my main takeaway has been one of feeling grateful to be able to stand on the shoulders of Tom Frost—and many others who have since followed in his footsteps—and document an exciting moment in Yosemite’s incredible climbing history.

There’s also a parallel with Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson and how their climbing achievement is also the result of the climbing pioneers who paved the way for big-wall free climbing before them: the Huber brothers, Paul Piana and Todd Skinner, Lynn Hill, Max Jones and Mark Hudon—all the way back to Tom Frost, Royal Robbins and Chuck Pratt.

In Ascent magazine, Tommy once wrote: “Embracing all styles of climbing made me the climber I am today. Style is a body of knowledge and a collective, generational work in progress. Nowhere is this truer than in big-wall free climbing.”

The same could be said of photography: that it’s a generational work in progress. This image that I took of Tommy and Kevin on the Dawn Wall isn’t mine, per se. It belongs to all those photographers who came before me and have inspired me over the years, including Glen Denny, Galen Rowell, Greg Epperson, Jim Thornburg, Beth Wald, Brian Bailey and Bill Hatcher. And it belongs to all those who’ve come up since: Keith Ladzinski, Tim Kemple, Jimmy Chin and Andrew Burr—among dozens of others who have simply been, in Tom’s own humble words, nothing more than climbers with a camera in tow.

Today the Dawn Wall is the hardest route in the world. But tomorrow, there will be some new stronger climbers who climb it faster and in better style. And of course, the same will be true with adventure photography. We are all standing on the shoulders of those whose hard work and fresh creativity came before us. And it’s our duty to stand as tall as we can, push the limits as high as we can, and wait to see what incredible climbs and visual storytelling tomorrow’s generation will bring.

Featured image: Nikon D4s / 14-24mm f/2.8 lens / ISO 200 / 1/1000th second / f/8

9 comments

Great piece, Corey- wonderful insight- thank you for sharing and taking the time to help us understand what and who went before. You are a beacon.

Great article Corey, thanks a lot. I’m an admirer of Tom’s works, thanks.

He’s a co-founder of Chimera? WHAT?!? I’ve been shooting for only 9 years, 7 as my income, but I never knew that. Climbing half my life now…really cool piece of info, and unexpected convergence. Thanks! Back to the article.

I have admired these Frost pictures since I first saw them over 50 years ago, but I did not realize that the first ones were shot with Bill Feuerer ‘s camera. I warmly remember Bill (the Dolt) from when I used to buy the gear he made from his Quonset hut down on Sawtelle in West LA. I still have my “Dolt” hammer holster.

Beautiful piece. Thank you.

[…] hanging off of the side of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park for ten days as he documented the hardest rock climb in the world. So when Google made the decision to bring their popular “Street View” technology to El […]

[…] hanging off of the side of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park for ten days as he documented the hardest rock climb in the world. So when Google made the decision to bring their popular “Street View” technology to El […]

Wow – that’s really impressive! I love that he just had a natural affinity for photography and used his passion for climbing as the impetus for his photographic work. Excellent post!

Excellent write up Corey. I saw the NYC Premiere of “Reel Rock X” a few nights ago here in NYC and was stoked to see some of your work on the big screen on the Dawn Wall segment, also can’t wait to see the full feature-length documentary film. Cheers man!

Comments are closed.