Nikon F4 Film Camera / Fuji Pro Velvia 100 ISO Film / 20mm f/2.8 lens / Speedlight SB-24

PART 1:

If you were to ask me to describe, in one word, what drives me, what incites me as professional photographer, the simplest answer I can come up with is: Story.

As is the experience of most children, whose fathers are the first (and often remain the best) storytellers of their lives, I was a kid who lived and dreamed every minute within the comic, frantic confines of my father’s tales. By age 7, I was sitting around with my dad and his scuba-diving pals, absolutely engulfed in their masterful stories of weekend adventures spent exploring the deep sea. These experiences instilled in me an early sense of story, a respect for originality, and a longing to have my own adventures.

Since then, I’ve told thousands of my own stories—usually at the end of a long day’s photo shoot while standing around with a group of friends and associates, enjoying that first well-deserved beer. Among all those tales, there’s one story that people have told me is particularly good—the one about the shot that launched my career.

At a basic level, it’s just a story about a dirtbag college kid who loved taking pictures and climbing rocks and then got lucky.

But on a deeper level, it isn’t really a story about me—not exactly. It’s a story about the awesome power of photography. It’s a story about following passion and seizing opportunity and working to create meaning. It’s a story that proves that even a single photograph can change a person’s life.

PART 2:

Climbing and photography were the two passions I discovered for myself, at age 13, and they continue to light a fire within me today. What’s interesting is in some ways, I’ve always viewed them as being hopelessly inseparable from one another. One offers a way to have experiences; the other offers a way to share them, make sense of them. To make those experience into stories. Without each other, the two are somehow diminished ventures.

As a freshman, I entered San Jose State with aspirations of becoming a photojournalist. After completing four semesters of school, I packed my climbing gear, camera gear and 100 rolls of film in to my Honda Civic, and set off to document rock climbing in the American West and meet all the derelicts and characters that make this sport so great.

The images I took on that trip opened a door for me with climbing magazines, and with the clothing company Patagonia. The photo editor at Patagonia, Jane Sievert, recognized the authentic moments of climbing and lifestyle that I’d worked so hard to create and began using some of my pictures in their catalogs. I always knew climbing and photography were intertwined within me as personal passions; but now I began to see how they could also work together for me professionally, too.

That climbing road trip, as all climbing road trips are prone to do, changed me in profound ways. I began to sense that life wasn’t lived in the classroom. There was real living to be done “out there”—in those unfathomable, dark places that my father and his friends used to dive to each weekend, and on those soaring, steep rock walls that I longed to climb.

Yet I was still a kid. I wasn’t quite confident enough in myself to jump down that rabbit hole yet. I was torn. Should I put nose to book, or foot to gas pedal?

After my big climbing road trip, I returned for my third year at San Jose State and found myself living in Markham Hall with an eclectic group of likeminded guys, one of whom was Tom Bulow, a big-wave surfer from Southern California. Tom was studying to become a physician’s assistant, but really it was riding waves that brought him to life. We hit it off because, although climbing and surfing are technically different worlds, at their core they’re the same in that they propose nearly identical answers to the big question: How does one live life?

Tom got a tip that a huge swell was hitting mainland Mexico. On a whim we decided that we should drive down to check it out. We shared a philosophy that when opportunity knocked, school became secondary. Our GPA really reflected that philosophy, too, though Tom, who’s much smarter than me, hid it better.

Anytime you go to Mexico, whether it’s for climbing or surfing, you need to be prepared. We loaded up Tom’s pick-up with camping gear and photography equipment, and strapped six surfboards to the truck’s topper. With $800 between us, we divided the money up into eight sums and hid each stash throughout the truck.

In Mazatlán, the federales held us at gunpoint while they searched our car for drugs. We had to bribe them with $150 and some traveler’s checks we knew they’d never be able to cash to let us continue. Then, in one of the biggest asshole moves all time, the federales dumped a bag of their own weed all over the seats of our truck so that we’d be hassled and jailed should we get stopped at future check points. The corrupt cops laughed as we pulled away and continued down the coast, heading toward the tiny fishing village of Pasquales.

Once in Pasquales, we discovered there was no real infrastructure to support the visiting gringo. This was no destination resort. There was one cantina, where we ate all three meals, and one hot mosquito-infested motel with rooms made of concrete walls, no windows and metal doors. It made Alcatraz look like the Ritz-Carlton.

I’m no surfer, but I still had fun thrashing around in the wake of the much larger waves that Tom could carve down. I shot photos of Tom wearing the latest Patagonia board shorts, which Jane Sievert had shipped to my dorm room the day before we’d left. Though we were sleeping in what amounted to a jail cell and our faces were pock-marked with mosquito bites, the beer was cheap, the food was delicious, and the surfing was great. And I was getting to capture the whole adventure with my camera for Patagonia. Life in Pasquales was pretty sweet.

Then Tom got stung by a school of jellyfish and went into anaphylactic shock. Suddenly this laid-back surf trip became a life-or-death situation. I ran up the beach for help.

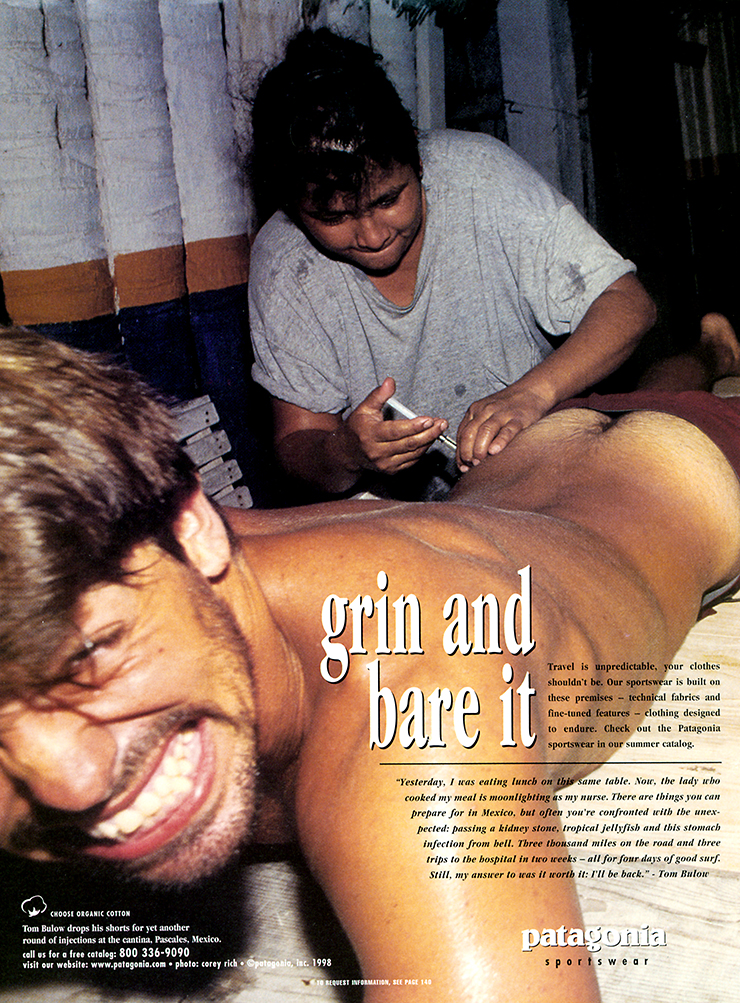

It turned out that the only person in Pasquales who could administer an injection was the waitress who had been serving us breakfast, lunch and dinner for the past week. We shuffled Tom into the cantina and laid him down on that table. The waitress pulled Tom’s board shorts down and administered the injection while I snapped two pictures, using an on-camera flash to light the dark room.

Tom survived the experience but the surfing part of the trip was now over. We packed up the truck to begin the long drive home.

Just before we left, I stood ankle-deep in the ocean to snap one last picture of this beautiful place with my Nikon F4 camera. After Tom’s episode, I felt very serene and full of appreciation for life while standing in that warm, clear water. Then a rogue wave came out of nowhere and knocked me over. The water ripped the glasses off my face and carried them out to sea. All I had left was a pair of prescription sunglasses, which I subsequently wore while pushing through 36 hours of non-stop driving to get us first back to a United States hospital.

A few days later, I found myself back in the classroom, nose to book. Tom, too. I shipped my film from our ill-fated trip to Patagonia, never expecting anything to come of it. The way it would work is that Patagonia would develop my rolls, make selects and put those into slide mounts; then they’d ship the other exposures back to me.

When Jane called to ask about why Tom was lying on a table with his pants down, I told her the whole story and, of course, she loved it. A couple of months later, I was blown away when I discovered that Patagonia decided to run that shot of Tom getting a shot in the ass as a full-page ad in Outside Magazine.

Photographically speaking, this shot is one of the crappiest photos I’ve ever taken. It’s all blown out. It’s actually a horizontal that had to been cropped to vert. I wasn’t thinking about composition and, in fact, I barely remembered even taking it.

It’s a testament to the values of Patagonia, and especially to the editing talents of Jane Sievert that she was able to sift through hundreds of exposures of surfing in beautiful golden light on a rare Mexican beach, only to choose this harsh, poorly lit horizontal snapshot of a bare-assed man with a swollen face—and then, to work her magic and turn that shot into a successful full-page ad in a huge magazine.

The photo was certainly gritty and raw, just what Patagonia was looking for. It lacked finesse and technique of a more seasoned photographer, but it contained the elements of that most prolific art form: Story. Wrapped within this shot of Tom lying on a table, getting an injection of epinephrine in his ass, was a story that transcended details and rose to capture the emotional essence of what it means to be a dirtbag, on a road trip adventure, in pursuit of big waves and steep rock.

You might think that landing a national print ad would’ve been the happy ending to this jinxed Mexican adventure. But compared to what happened next, it turned out to be only the beginning.

PART 3:

Sometime in the interim, I transferred to Fresno State, but that one question I always asked myself remained the same: Nose to book, or foot to gas pedal?

It was1996. Though I didn’t know it, one day, while I was probably sitting in my dorm room writing a paper, a guy named Brian Terkelsen was enjoying a first-class flight from Europe back to the United States.

The dot-com boom was right in its prime. And Terkelsen had just helped launch a new online venture, Quokka Sports, with lofty ambitions of being the world’s premier digital sports media company. Quokka’s websites were cutting edge in terms of functionality and design. They covered everything from climbing on Trango Tower, to the America’s Cup, to even the 2000 Olympics in Sydney.

But before all that, one of their first productions was going to be covering an upcoming 30-day foot adventure race across Morocco.

As I said, I didn’t know any of that. Then, one day, I got a call. I was sitting in my dorm room, scheming my next road trip, when the phone rang.

“Hello, this is Corey Rich,” I said, by now knowing enough to at least answer the phone professionally. It was a Brian Terkelsen’s assistant from Quokka Sports—two names I pretended to know.

“Mr. Terkelsen saw your photograph in Outside Magazine on his recent flight home from Europe,” she said, referring to the Patagonia ad of Tom. “This is exactly the kind of storytelling we want for our company, Quokka.com. We think we might have an assignment for you in the Sahara Desert of Morocco. Would be able to come down to our office in San Francisco tomorrow to discuss?”

Of course, I blew off all my classes and actually drove to San Francisco in my Ford Econoline van that night. On the drive, I used my first-gen, two-pound brick cell phone and called up the one photographer I knew who was big-time, a San Jose State alumni that all of us looked up to: Brad Mangin, a photographer then shooting for Sports Illustrated. Brad always gave me straight-up advice. I’d send him photos and he’d tell me what was good and what was shit, never sugar coating anything. I valued his advice as if it were a canteen of cold water in the desert.

Because I’d only ever shot on spec, I didn’t know what to say if Quokka were to offer me an assignment. I didn’t know how to price myself. I asked Brad.

I could hear through the phone that Brad’s friends were over. In the background, a bunch of dudes sounded like they were playing cards and drinking beers. I could tell Brad didn’t really want to talk to this green-behind-the-gills college kid.

“I dunno, just tell ‘em a thousand bucks,” he said. “Listen, Corey I gotta go, man. Good luck.”

Wow! I thought. If I could make $1,000 AND go to Morocco … I mean, I would’ve paid THEM $1,000 to let me go shoot in the desert! My head was still spinning as I parked the van directly outside of Quokka’s building around midnight, crawled into the back and tried to go to sleep.

The next morning, I woke up early and “showered” in the streets, dumping a gallon of water on my head. I put on my nicest shirt, grabbed my portfolio—which was really just a bunch of pages torn out of climbing magazines and Patagonia catalogs—and walked into Quokka Sports’ headquarters.

I was led into an incredible top-floor conference room containing walls of windows that provided a stunning panorama of the whole San Francisco Bay. Herman Miller Aeron chairs surrounded a long table and were filled with a bunch of young executives, all in their 20s and 30s, all titans and engineers of the dot-com boom.

We talked about the job: a 30-day adventure race in Morocco. They wanted to use state of the art satellite equipment and the latest digital cameras to upload live media of the race to something called the “world wide web.” It was an ambitious undertaking for the time, with virtually no precedent.

I passed my portfolio around the table, talked about my photography background and tried not to show how nervous I was. Finally, my portfolio made it to Brian Terkelsen, the VP who had first seen the Patagonia ad on the plane. He flipped through my portfolio, and stopped on my shot of Tom. “This photo is why you’re here,” he said. “We loved this photo. And we think you will be the right person for this job. But the big question is, ‘What do you cost?’”

At this point, I was so nervous and desperate just to lock down the deal that it took everything in my power not to blurt out, “I’ll do it for free!” Instead, I took Brad’s advice and, with bated breath, said, “I’m $1,000.”

The room went dead silent. It felt like we were all standing in a funeral home and, with those few words, “I’m $1,000,” I’d just tipped over Grandma Terkelsen’s casket. Desperate to save face, I was on the verge of blurting out a quick price readjustment to $500 when Brian beat me to the punch.

“Ooh, that’s pretty steep,” he said. “We were thinking $800.”

Now, I’m thinking, “This is fucking awesome! They’re going to pay me $800 to go to Morocco!” But again, I stayed silent … mostly because I just didn’t know how to respond. I didn’t want to seem too inexperienced, too gleeful … too anything. I didn’t want to make a wrong move and blow it. And in spite of myself, that worked out in my favor when, once again, Brian beat me to the punch.

“ALL RIGHT, GOD DAMMIT, $900 a day, but you do realize it’s 30 DAYS!?”

And then it hit me. … We weren’t talking about $900 total. … He meant $900 times 30.

Finally, I managed to summon some words. “That works for me.”

When I think back to that moment, I wonder if I had had my iPhone instead of that two-pound brick cell phone, what I might have done. I think I probably would’ve sent a group text message to my mom, dad and the dean of journalism at my university that just said, “I’m out! Done with school! Laters!”

Morocco was an amazing trip—one of the coolest adventures and coolest assignments I’ve ever had. By today’s standards, producing videos and uploading photos to the internet via satellite is hardly impressive, but back in 1996 it was a big deal. There were about 15 of us handling the video shooting, producing, writing, photography and satellite transmission—and all of those individuals were super talented in their specialties.

When I got home, I took that money I made and bought my first house. And while I ended up going back to school for a bit, it was short lived. Three classes shy of a degree, I dropped out. I didn’t have time for school because I was already doing the job I was studying to do.

This is my story of how, through one unlikely image, I was able to launch a career in professional photography. Yet, I wonder: Is there anything useful or meaningful to take away from this particular story?

There’s no college photography course out there that tells students to go to Mexico, get held up at gunpoint, surf big waves, survive an anaphylactic reaction to a jellyfish sting, lose your glasses and drive home with a bunch of rolls of film containing one of your worst-ever exposures which will, against all odds, become a national ad, which in turn will be seen by an executive who will offer you the biggest, coolest photo gig of your life. (Although maybe there should be … I certainly would’ve stayed in school longer had that been the curriculum.)

It’s hard to know what to make of all this. Is the greater lesson to just follow your passion? Do what you love? Somehow that feels a bit cliche or cheesy.

Again, I return to that one word: Story.

The critic Kenneth Burke once said that “Stories are equipment for living.” And I think that idea really encapsulates what being a photographer, and even a climber, is all about. You have to follow your passion and do what you love, of course. But the other necessary ingredient is being able to take those impassioned experiences and wild adventures, and make meaning out of them. Through Story. Written. Still. Motion. Audio. Whatever. All of it.

When I look at this unlikely picture of Tom, part of me is slightly chagrined to admit this is the photo that launched my career. Yet there’s a bigger part of me that loves that. It’s a reminder that photography is not about having newest, most expensive camera or the fastest lenses. It’s about having the “equipment for living,” about getting inspired to go out every day and live and create and breath life into your own stories, the way my dad and his friends would do every weekend, and the way I aspire to do each day with my camera.

And the most fun part of the whole thing is seeing where your work will go, and discovering where that one unlikely picture will take you next.

15 comments

I think at its fundamental level, the crux of our un-fair practices comes in two waves: First, physical incapability due to technological limitations and second, our own aversions and/or lack of awareness to “ego death”, which can allow us to closely examine ourselves from a distance, establishing a “blank slate” in our assumptions of reality so that we can begin to align ourselves and adapt to the natural order of things. This can bring us closer to a state that can maximize our collective survival.

The biggest mistake we’ve ever made was in defying nature before we were ever capable of doing it. To assume that our problems are mostly constructed by a social environment is to assume that one can simply re-imagine themselves and suddenly change into a different person and to assume this means that you’re ignoring reality and constructing it on your own accord…Now, isn’t that what we’ve already been doing for thousands of years?

I guess the point I’m trying to make is that you shouldn’t be afraid of differences and you shouldn’t be afraid of cold-hard facts about reality because it’s those cold hard facts that can allow us to reconcile our own destructive powers with what is so that we can actually come up with real societies that are genuinely cool with different people.

But above everything, if you’re in a position of power or privilege, utilize that with everything you have to develop technology, businesses, and ideas that can unionize the false dichotomy between nature and nurture, which has been haunting us for far too long.

Beautiful dude. A great story well told. Thanks for the inspiration.

Dear Mr Rich

As a not so young becoming an adventure photograph dreamer, until today I was just pleased by you Behind The Shots stories, even if I felt there was much more than cool stories.

Today I feel I have to tell you I am blown away by this last one, I now understand that more than photo lessons you give your readers true, deep, subtle and powerful lessons of life.

Thank you for what you do on this site, if one day I manage to sell one photo just know you would be a part of it.

Respects,

Julien

PS : sorry for my limited english, I sometimes have to assume being french

Dear Corey,

I must say that you are a wonderful writer too. I thoroughly enjoyed your “story”, and it is really inspiring. I am a journalist based in Mumbai with deep love for photojournalism. “It’s about having the “equipment for living,” about getting inspired to go out every day and live and create and breath life into your own stories, the way my dad and his friends would do every weekend, and the way I aspire to do each day with my camera” is something I completely agree with, and often tell my photojournalist friends that they are not doing this enough. I am part of a collective trying to create a national level platform for Indian photojournalists to showcase their work. In last three years, we have managed to organise an annual contest, raising funds from corporates and giving them away to photojournalists. if interested, you could check http://www.mfi.org.in

Thanks so much

satish

Great story. This will teach us and our kids after I read it to them to follow your dreams and

That was truly inspiring! made me wanna load up the car and go on a skate trip of a lifetime. With a story like this, your dad must be proud you followed in his footsteps with great story telling.

Wow. Thank you so much for the story. Thats for the inspiration and honesty in it. God Bless you.

Thanks you all for the kind words! It means a ton to me that folks are actually reading these tales and more importantly getting a bit of inspiration out of them. Certainly fuels my fire to continue writing and sharing. After all that’s what it’s all about!

Cheers!

Corey

This story is amazing! And very inspiring for a second year photography student and an active climber. Even though I’m currently at a fine art degree, photojournalism is something I’d love to do in the future.

Thank you so much for your absolutely stunning story!

Stories of turning passion and personal work into a career never gets old. And the defining moment photo of Tom getting a shot—in all its technical imperfections—”captures the magic.” Great stuff.

This post reminds me of that line in a song Jimmy Buffett sings, “If you ever wonder why you ride the carousel, you do it for the stories you can tell.”

But the hidden lesson here Cory is that as a college student you packed 100 rolls of film “and set off to document rock climbing in the American West.” If you were shooting chrome that was around a $1,000 investment in film alone. That’s a commitment to craft.

I’ll never forget reading where the great adventure photographer Galen Rowell spent ten years as a mechanic (shooting climbing photos in his spare time) before he was able to turned his passion and personal work into a career.

Thanks for the story, just what I needed right now!

Wow that really brought back a flood of memories! Thanks Corey! You couldn’t have told that story any better. I’ve been back there a few times and have had nothing close to the indelible experiences of that trip.

Apart from your two great skills, you’re also an amazing writer/story-teller.

Corey,

I was first introduced to your work through the recent Nikon promos and really enjoyed the work and was curious about who you were. I looked through your portfolio and was impressed and inspired by the quality. Yet, I also detected something deeper in the images – a sensitivity that was more than photography principles. Now, after reading this blog post and your write up on the Climbing cover, I see it. Your mantra of ‘Story’ is exactly what drives me. I have been fascinated by it since a child and only recently have I discovered outlets to bring the stories out of my head. Thank you for sharing who you are and how you came to be. I am on a similar path of passion.

[…] His background story is what really gets me going though. His career took off after an ill-fated surfing trip to mexico where he was not only held up at gunpoint by federales, but also had to help his friend who was stung by a school of jellyfish and began to go into shock. The tiny village they were in only had one person who knew how to administer an injection, and it was the waitress at the cantina they had been eating at. They rushed to the cantina where the waitress proceeded to give his friend the shot, and Rich snapped a quick photo of his buddy, pants down, getting a shot in the ass by a waitress. He thought nothing of the photo other than that it was funny and a good story, but when he sent the film in to Patagonia, they immediately asked about the picture. After hearing the story, they used the photo in a full-page advertisement and from there, Rich’s career took off. You can read the full story here: https://news.coreyrich.com/2014/02/story-behind-the-image-that-launched-my-career/ […]

Comments are closed.